Captain Gregg W. Baumann, U.S. Navy, Director of Ocean Engineering, Supervisor of Salvage and Diving. shares with MTR insights on the long and proud history regarding difficult missions accomplished, including most recently the location and filming of the lost TOTE containership El Faro.

What, specifically, is the scope of the responsibility of the Supervisor of Salvage & Diving; Director of Ocean Engineering?

The responsibilities of the Supervisor of Salvage & Diving; Director of Ocean Engineering (SUPSALV) include being the Center of Excellence for diving for the Department of Defense (DoD), the system safety certification authority for DoD diving and manned hyperbaric equipment, the technical authority for military diving equipment, the technical authority for underwater ship’s husbandry repairs and inspections, and salvage; By authority of the “Salvage Facilities Act” (10 U.S.C. 7361-7364) SUPSALV provides salvage facilities for public and private vessels and provides Admiralty legal support to settle claims for salvage services rendered by the Navy. Within the context of this authority, SUPSALV provides for the equipping and maintenance of a national salvage capability for use in peacetime, war, or national emergency.

To put your office into scale and scope. Can you please give an overview of the personnel and physical assets under your guidance.

SUPSALV has more than 565 military, civil servants, and full time contracted employees supporting our Washington, District of Columbia headquarters office, our Naval Experimental Dive Unit research laboratory in Panama City, Florida, our deep ocean search and recovery equipment program, our Emergency Ship Salvage Material (ESSM) warehouse system, diving engineering services, and our world-wide, underwater hull cleaning services for fleet vessels. Our facilities include a headquarters office, eight ESSM warehouses and support centers around the world, a Deep Ocean Search and Recovery warehouse and engineering facility in Maryland, and diving services support offices in Virginia, California, Hawaii, Japan, and Bahrain. Our inventory of search equipment, diving support material, oil spill recovery equipment, and spares total more than 30,000 items, more than 500,000 sq. ft. of facilities, and a world class diving and equipment research facility. SUPSALV maintains national mission assets of search and recovery systems with capabilities ranging from shallow water to 20,000 ft. that include the Towed Pinger Locators, towed Side Scan Sonars, and Remotely Operated Vehicles. Additionally, we maintain three worldwide commercial salvage services contracts for which we can immediately surge in personnel and equipment. Our annual average operating budget is approximately $110-120 million, but increases significantly when we conduct large reimbursable salvage and oil spill operations. The value of our non-facility related inventory is in excess of $110 million.

We understand that you assumed this post in October 2014. To date, what do you find most rewarding? What do you find most challenging?

What is most rewarding and most challenging is one in the same. Specifically, SUPSALV is the backbone for providing the U.S. Navy fleet with diving support and salvage capabilities as a national level first responder. Providing all of these services on a daily basis so that the Navy fleet can maintain its strong military presence at sea and keeping our sailors, airmen, soldiers, marines, and guardsmen safe is what drives me each and every day. However, meeting all of these challenges with limited budgets and resources, requires making difficult decisions to keep the warfighter prepared and safe while still operating in a difficult fiscal environment. Helping our forces accomplish their missions safely and effectively is the reward for our team’s hard work and diligent efforts.

For the context of this interview, we are most interested to focus on salvage and diving safety. Given that scope, could you share with our readers a ‘case study’ or two which you feel best exemplifies the capability of your office?

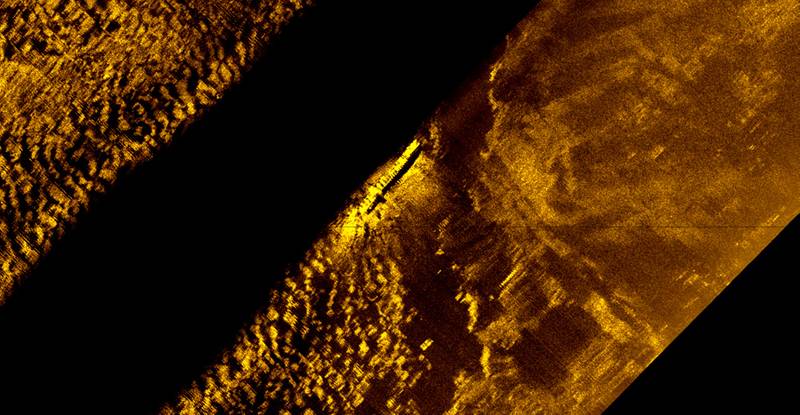

First, I’d site two recent marine incidents. The first is the M/V El Faro which went missing on or about Oct. 1 in the Bahamas. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in the conduct of their safety investigation deemed they needed SUPALV’s experience and resources. With our long standing working relationship, we quickly partnered and developed plans to search for, locate, conduct a Side Scan Sonar survey of the accident area, video document the ship, and retrieve the ship’s Voyage Data Recorder (VDR). Utilizing our 20,000 ft. Side Scan Sonar “ORION”, our 20,000 ft. Remotely Operated Vehicle “CURV”, and the Military Sealift Command’s ocean going tug USNS Apache (T-ATF 172) we mobilized and satisfied three of the four objectives within just a few weeks. Unfortunately, we have yet to be able to locate the VDR. The accident is still under investigation with the NTSB and United States Coast Guard.

A second salvage example would be the successful removal of USS Guardian (MCM 5) in 2013. The ship unfortunately ran hard aground on Tubbataha Reef in the Sulu Sea in the Philippines. Due to the sensitive reef environment, the inability to access the vessel with large removal equipment, monsoon weather and seas, SUPSALV brought together a team of navy divers, a navy salvage ship, salvage engineers, and commercial salvors to safely remove the ship from the reef by cutting it up. Balancing environmental concerns, effective salvage plans, and political sensitivities, SUPSALV safely sectioned the ship into four 250-400 ton lifts, and removed the ship without causing any further damage to the reef or allowing the release of pollution or hazardous substances into the environment.

Your job by its inherent nature is a dangerous one. Put the emphasis on safety in perspective.

On diving safety, personnel safety is always the primary consideration. This involves ensuring safety is paramount in both the design of Divers Life Support Systems (DLSS) as well as diving operations themselves. We ensure safety is designed into, tested for and eventually certified in all of our DLSS. Tragically though, we lost four sailors in diving accidents in 2013. As a result, we conducted a strategic assessment of the safety of diving operations throughout the Navy. SUPSALV co-chaired a Diving Operational Assessment Integrated Project Team that conducted a holistic review of Navy Diving Program compliance with requirements with particular focus on supervisor accountability. Integral to this effort was an assessment of the culture within the diving community, as it affects our ability to adequately assess operational readiness, effectively plan missions, accurately apply operational risk management, safely execute dives, and apply lessons learned. The findings of the review found: Navy diving continues to meet Combatant Commander requirements and supervisory accountability, and that navy diving is effective. However, there were specific areas that were deemed to need improvement: improve supervisor decision making, development, qualification, and proficiency; build effectiveness in command level diving assessments; become a self-learning organization; establish better diving mishap reporting and trend analysis; and update the Navy’s diving program instruction.

Marine Salvage is an intriguing business, literally an engineered solution as no two wrecks are the same. In your career, what one technology do you count as having the greatest impact on allowing salvage to be conducted more efficiently and safely?

Unequivocally, it’s the improvements in the area of information technology that have had the greatest impact in our response capability. In most cases the physical rigors of salvage are basic, rudimentary, and don’t have huge strides to make with the increase in technology. However, the software tools now immediately available to the salvor are game changers. The software packages available today have the capability to rapidly perform very detailed and complex analyses of vessel loading, stability, and structural characteristics for intact, damaged, and grounded vessels and evaluate these properties over the full range of salvage operations. Within SUPSALV, we use a Navy unique software package, Program of Ship Salvage Engineering or “POSSE” for short. As IT systems continued to grow, SUPSALV teamed with a commercial vendor to jointly fund and develop POSSE. It has given us the ability to fully model every ship in the Navy inventory. As a result, when a salvage incident does arise, within minutes we have our engineers conducting risk assessments, developing salvage plans, and providing understandable engineering solutions to complex, and multi-variable problems.

When I speak to commercial salvors, most cite the increasing size of ships as one of their top challenges today, as quite simply ships and cargo capacity are growing larger, faster, than the salvage capability to assist them in time of need. With that as a backdrop, how is the market changing to present challenges to your office?

As it relates to SUPSALV’s participation in the salvaging of commercial vessels, the increased size of ships is certainly at the top of the list of challenges. However, as it relates to SUPSALV’s overall salvage operations, it’s the increased focus on minimizing damage to the environment and pollution discharges while conducting the salvage. As a result SUPSALV regularly conducts spill exercises with the fleet, provides on-going hands on and table top training, and maintains one of the largest oil spill equipment repositories around the world in our ESSM system.

We cover Navy and Government vessels in our pages regularly, and to say current government spending is “challenged” at the moment is an understatement. From where you sit, what are your funding issues, if any, and how has this had a material impact on your service.

The center focus of the Navy budget every year is shipbuilding and the 30 year shipbuilding plan. Since the Cold War ended, the Navy’s inventory of ships has dwindled and replacement with more complex technologies has become more expensive for the same size of vessel. As a result, finding the right balance of ships in the 30 year shipbuilding plan has become increasingly challenging. Our current inventory of four tugs and four salvage ships is aging and will require replacement in the not too distant future. How the Navy will replace this capability to meet the fleet mission requirements is still being discussed.

Looking at your career, please explain in as much detail as possible the most difficult or challenging dive or salvage operation, explaining why.

The operation that clearly stands out the most to me is the salvaging of the Japanese high school training fishing vessel, F/V Ehime Maru, and recovering eight of the nine souls lost off the coast of Hawaii in 2000 ft. In 2001, one of our submarines tragically hit and sunk the Ehime Maru during a routine training exercise. Showing true sorrow and good will to the Japanese families who lost loved ones in the incident, President Bush promised to do everything possible to recover those who were lost. In looking at the possible solutions at this depth, we came up with few alternatives. At 2,000 feet, we couldn’t find anyone certified to conduct saturation dives to this depth. We then looked at the idea of penetrating the ship with ROVs. This option was ruled out due to the high probability of ROV entanglement and inability to access the entire interior of the vessel. The solution we eventually arrived at was to place two straps beneath the ship, lift and suspend the ship beneath a ship on the surface, then carry it to shallow water where we could safely and effectively dive on it. A salvage of this nature had never been accomplished before so we were developing innovative solutions as the operation progressed. To obtain expertise conducting complex operations at this depth, we turned to the deep ocean oil field support companies.

Teaming with a handful of these companies and a commercial salvor, we successfully placed two straps underneath the ship and brought the ship into a depth where we could dive on it. This operation was by far the most difficult in my career due to the depth of recovering the ship and use of ROV’s to do so, the political sensitivities involved between the two governments, the cultural sensitivities involved, the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks taking place while recovering the ship, and most importantly the human compassion involved in trying to help the nine families. In the end we were only successful in locating and recovering eight of those lost. In the 29 years I’ve served in the Navy, the memory that has etched itself the deepest in me was notifying the family of the 9th victim that we were unable to locate their teenage son.

(As published in the January/February edition of Marine Technology Reporter: http://www.marinetechnologynews.com/magazine/issue/201601)

February 2025

February 2025